John E Gunter: Talented Entrepreneur Established Sawmill in East Baldwin

by Brian Swartz

When a Long Island real-estate developer needed white pine boards for the thousands of homes being constructed in New York by his company, he turned to an East Baldwin sawmill operated by a far-sighted Cumberland County entrepreneur.

Born in Portland to John “Jack” E. Gunter and Agnes Louise Gunter on September 5th 1940, John Ernest Warring Gunter lived in the Forest City until his “parents built a house on top of a hill in Gorham” in 1952. Actually Canadian citizens, Jack Gunter and his two brothers were cutting trees in the Gaspe Peninsula forests in New Brunswick when they, along with their father “came to this country in 1934… to see if they could get into the lumber business here,” John said.

Immigrating from Saint John, Jack and Agnes Gunter settled in Portland in 1936. Jack and his brothers built a sawmill at Steep Falls on the Saco River. To help bring logs to the mill, Jack was involved in river drives: he “was the last guy to drive logs down the Saco River,” John recalled.

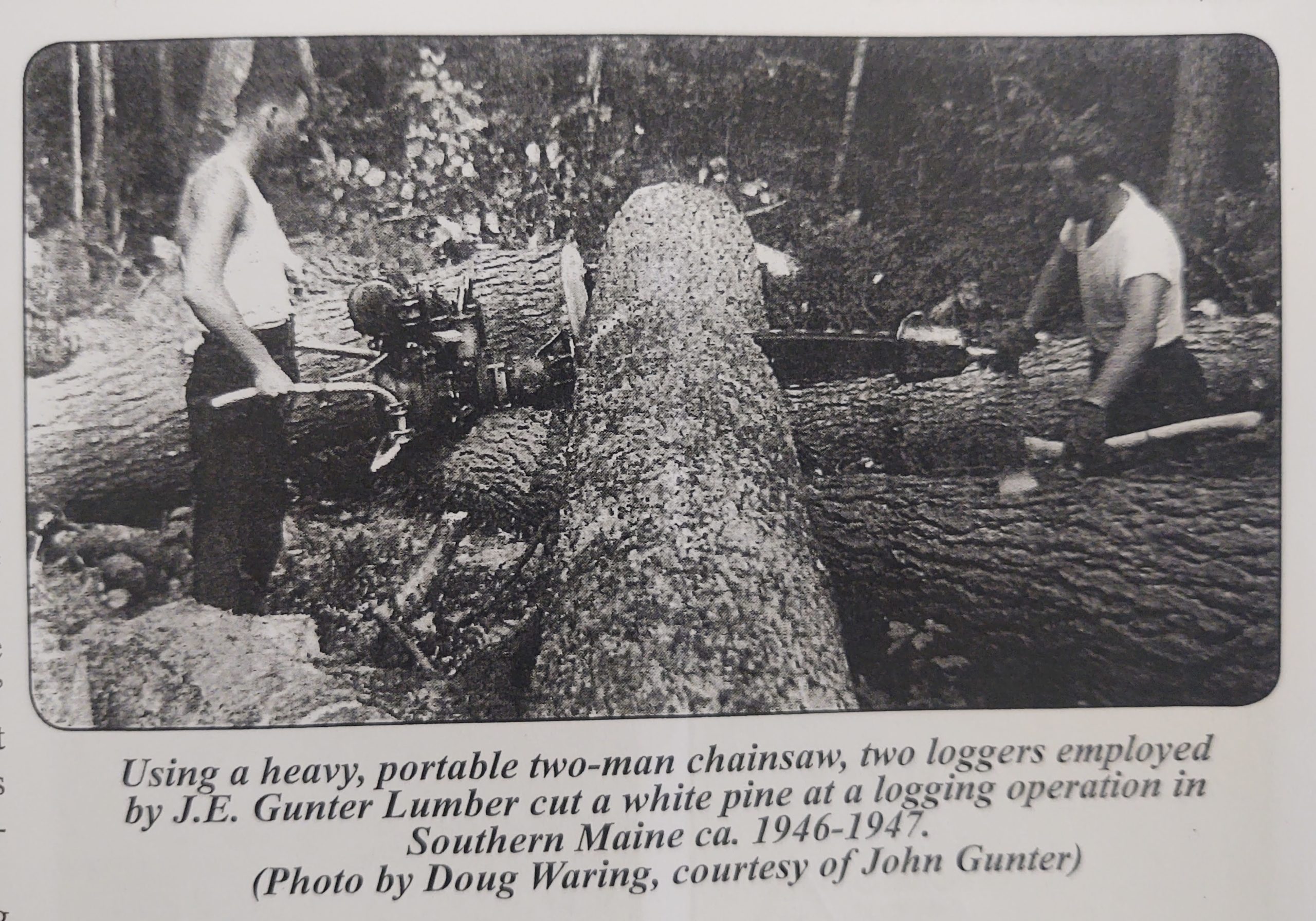

While the Gunters’ were running their Steep Falls sawmill, the Great New England Hurricane blew through Maine in September 1938. Although its winds had lessened by the time the storm tromped across southern Maine, the hurricane blew down countless trees in Cumberland and York counties, where Eastern white pine finds excellent growing conditions in sandy soil.

In 1939 the Gunter brothers obtained a federal contract “to saw hurricane pine,” according to John Gunter. His father started building a white pine sawmill in East Baldwin “from the ground up in 1940”; quickly becoming “the biggest knotty pine lumber mill east of the Mississippi,” the mill complex was operated as J.E. Gunter Lumber. The company later became the Sebago Forestry Corporation.

Located on Route 113 in East Baldwin, the sawmill employed many people, both in the woods and at the mill. “I used to go to the mill when I was 6, 7, or 8 years old,’ John said. “One thing my father gave me was the desire to work. “I started working [at[ a man’s job when I was 13 years old,” he recalled. “I went to work for my father at his lumber mill in East Baldwin.”

J.E. Gunter Lumber cut white pine for William Jaird Levitt, the Brooklyn, New York real-estate developer credited with creating the concept of American suburbia. After serving in the Navy in World War II, Levitt returned to New York and joined Levitt & Sons, a real-estate development firm started in 1929 by his father, William.

The company had focused on upscale NYC-area housing in the 1930ss, but Bill Levitt expanded Levitt & Sons into creating a massive housing development on Long Island immediately after the war. Involving approximately 17,000 new houses, that development became Levittown, New York; similar towns became Willingboro, New Jersey and Levittown, Puerto Rico. Applying an efficient assembly-line concept to onsite housing construction, Levitt & Sons “was the world’s biggest house-builder” at the time and J.E. Gunter Lunger ran almost straight tout to supply the pine boards needed by Levitt, John Gunter said. “They could build all those houses without any waste,” even at the East Baldwin mill, he noted. Shavings were sold to local farmers and other customers; sawdust fired the boilers that heated the dry kilns in which white plain boards could be dried in four days.

“My father had 85 people working at that mill,” which was located on a spur of the Mountain Division operated by the Maine Central Railroad, John said. The mill ran six days a week, and a crew operated the boiler house seven days a week to keep the dry kiln heated.

J.E. Gunter Lumber had portable sawmills in Denmark, Hiram, and Sebago, and Ken Mains operated a similar mill for Gunter Lumber in North Windham. Hollis sawyer Dan Haskell also supplied pine boards to the Gunter mill.

Besides owning thousands of acres of valuable pine, Jack Gunter kept an eye out for ways to improve the sawmill operations and his product line. Besides developing the dry kilns that exponentially increased the mill’s lumber-drying capacity, circa 1947 he designed a plywood made out of wide pine boards. That new product went into kitchen cabinet doors and similar applications.

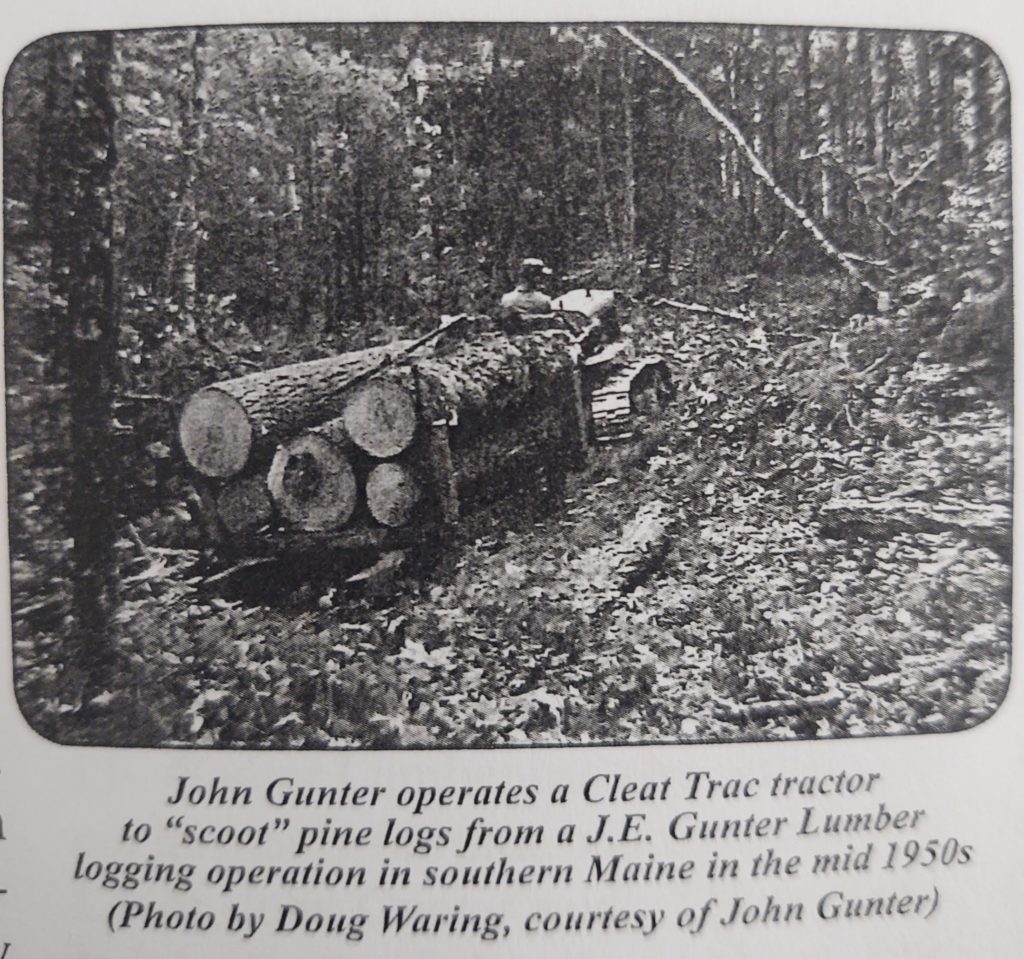

When he started working at the East Baldwin mill, John Gunter drove a yard tractor to place boards in the dry kiln. Still in school he worked on Saturday’s and during school vacations. “I really liked the business,” he said. “That is where I learned to like machinery; I scooted logs in the woods, and we had two big forklift trucks” that he would use to carry pine logs to the mill. John was 10 when his father gave him a 1½-ton “straight truck, a ford.” The truck needed some attention that John did not hesitate to give it; “that’s where I learned how to wrench (do repairs),” he said. The East Baldwin mill “had a big shop” in which “I learned how to weld,” John said. Pausing a moment, he smiled at a particular memory and then chuckled, “ I caught my hair afire” once while welding. “I had an education these other kids didn’t have in high school,” said John, initially a student at Gorham High School. When he started cutting classes to work on vehicles in a friend’s junkyard, “my parents jerked me out of there and put me in Fryeburg Academy,”

Jack Gunter sold his East Baldwin sawmill in 1957, “and it went downhill,” John said. The entire complex closed down in time, and the buildings gradually disappeared; today only a forlorn water tower marks the site where Sebago Forestry Corporation once stood.

John Gunter later became a truck driver. After driving for some years for Auburn-based Pioneer Plastics, he leased his truck to Scarborough-headquartered R.C. Moore Inc. Often making short hauls to Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, he has occasionally gone to California. John has driven 6.5-million accident-free miles. John enjoys spending time with his daughters, Carole and Katherine. Still going strong at an age when most men have long since retired, John said, “I love my job, love working for the Moore family. What I didn’t learn from my father, I learned from Richard Moore.”